A cinematic journey into the world of Venetian architect Carlo Scarpa and his passion for Japanese culture.

The Pavilion on the Water grew out of the filmmakers’ research, which led to the making of a short documentary on Carlo Scarpa (1906-1978) and Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694), La Pietà del Vento (2014). On his last trip in 1978 Scarpa intended to reach the ancient Japanese capital Hiraizumi. He was retracing the routes described by the poet in the travelogue he wrote before his death, The Narrow Path to the Deep North (1694). Scarpa never reached Hiraizumi; he died in a tragic accident in Sendai on the same day the poet died, November 28th.

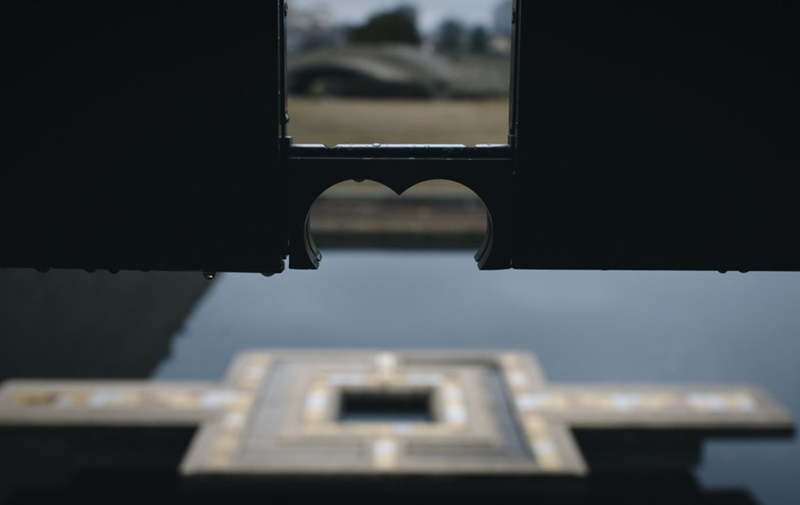

Reconciling a poetic aspiration, pandering to a lyrical and dreamy sensibility, with a philosophical approach, we wanted to recount the works of the Venetian architect, not only because of the high artistic value they represent, but also because of the nature of his figure as an emblem of a unique encounter between tradition and modernity, East and West.

Scarpa liked to call himself, “Byzantine at heart, a European setting sail for the East”.

The documentary ideally aspires, through the means of cinema, to manifest and evoke the research he worked in that direction.

The narrative is directed along an experiential itinerary, in which artistic, philosophical and literary suggestions, archival materials, thoughts and memories become load-bearing elements for the reconstruction of Scarpa’s cultured and emotional discourse.

In the belief that this narrative mode retains in itself a certain degree of exactitude, consistent with the intrinsic impossibility of circumscribing the existence and creativity of an artist in a complete and accomplished portrait.

And at the same time it is an opportunity to approach a discourse of universal scope, that of the essence of the work of art.

Scarpa’s work seems to insistently pose us this question, which, as in an enigma, demands to be solved. But the deeper we go into this attempt the more the mystery about it opens up. As if Scarpa’s work cannot leave us indifferent, and forces us to question ourselves continuously, on many levels, as artists, intellectuals, human beings. Although it is inextricably linked to the context in which it arose, it seems to present a force capable of speaking to us deeply, transcending geographical and cultural limitations. Just as to enter the tea houses built by Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591) it was necessary to lay down one’s arms and enter as an ‘equal’-not even the title of nobility had weight there-, in Scarpa’s architectures one enters with one’s mind and heart in a particular disposition. It is the places themselves that demand it, they themselves operate this transformation.